Research on Treatment Effectiveness

Trauma-Focused Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) is the evidence based treatment for children and adolescents, ages 3 to 17, with sexual abuse histories. TF-CBT uses a psychosocial model that recognizes that involving a non-offending caregiver in the therapeutic process increases the effectiveness of treatment.

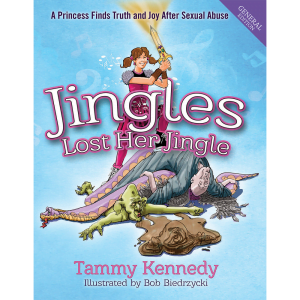

The research shows that interventions using puppets, art, games and stories are efficacious forms of treatment for children who have been sexually abused and traumatized.

Drawing, and other forms of play therapy such as clay and sand tray, provide a medium through which children can express thoughts and emotions for which they may not have the words or cognitive framework to describe the trauma they experienced.

It may also be more comfortable for the child to relate a personal trauma indirectly through a toy, rather than directly to an adult, because of the emotional distance and consequent safety that it provides. For example, the child can share a painful memory as happening to the doll. Another toy may be designated as the perpetrator. The child may administer punishment on a toy without fear of reprisal or fear of damaging an important relationship, allowing other, perhaps disowned, emotions to surface.

This process of imaginative play provides the therapist with the understanding necessary to provide individualized treatment and provides the child a path through which a sense of personal power and hope can be restored.

The term epigenetics is used to describe the way our environment can change the way our genes are expressed, at the moleular level, and thus change who we are as human beings, by manipulating our emotions and cognitions. More to come…

Managing the Intensity of Exposure to Traumatic Material

While some clients may experience relief after disclosure of a traumatic event, others may be overwhelmed by the emotions and body sensations related to the original trauma. In order to deal with the pain of re-experiencing, these clients may revert to the maladaptive behaviors previously used in dealing with the original trauma, e.g. self-medicating or self-harming. It is the responsibility of the counselor to manage the intensity of exposure to traumatic material in order to protect their client from retraumatization. This is accomplished by closely monitoring the client’s affect, such as overstimulation, and behavior, such as regression and dissociation. During the session, if a client remains numb emotionally, while relating a traumatic event, then ‘affect’ type questions may be asked, such as detailing sensory memories of the event. In this way the intensity of exposure is elevated. If, on the other hand, the client is beginning to exhibit signs of overstimulation, e.g. rapid breathing, agitation, then the intensity of exposure can be decreased by asking ‘content’ type questions that are not related to the trauma. Additionally, relaxation and breathing techniques and grounding exercises can be employed. The goal is to conduct the session within a therapeutic window, where the client is not over or under stimulated, to allow the processing of traumatic material. Ultimately, this means increasing the tolerance for exposure to the traumatic memory, reducing the intensity of the emotional response to the traumatic memory and allowing integration of the traumatic memory as part of their history.

Recent Comments